In October, there was an incident that calls into question the safe stay of spacecraft in geostationary orbit – the Intelsat 33e communications satellite exploded. Western experts prefer to use the term “disintegrated”, although, obviously, there was an explosion of the power plant of the European communication satellite, which led to the complete destruction of the apparatus. The explosion of the power plant of the European communication satellite resulted in the formation of more than 500 fragments that scattered in geostationary orbit, with some moving at a speed of about 500 m/s. This poses a threat to other vehicles in geostationary orbit, making it an unsafe place in near-Earth space.

The creation of multi-satellite constellations has led to an intensification of space launches and a sharp increase in the number of dangerous objects in low-Earth orbits. In other words, space debris that can damage, or even completely destroy, operational satellites. People considered the geostationary orbit (GEO) quite safe in this respect, as it is a higher orbit. Statistics indicate that the number of dangerous objects recorded in GEO is significantly less than in low-Earth orbits, but the geostationary orbit also offers limited usable space.

Therefore, even a small increase in the number of space debris fragments, especially those moving at a “killer” speed, can lead to catastrophic consequences here.

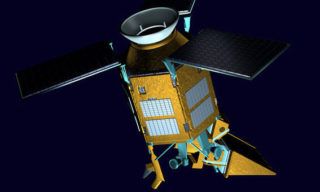

Intelsat 33e is a telecommunications spacecraft with a geostationary mass of about 4.3 tons (6.6 tons at launch), created by the satellite division of Boeing Corporation based on the BSS-702MP platform. In transport position, its dimensions are 7.9 x 3.8 x 3.2 meters, solar panels generate 13 kW of electricity, and the equivalent capacity is 269 Ku- and C-band transponders. It belongs to the HTS (high throughput) satellites.

The European Space Agency launched the satellite on August 24, 2016 from Kourou in South America using an Ariane 5 ECA launch vehicle. The satellite belongs to the satellite operator Intelsat. The estimated lifetime of Intelsat 33e exceeded 15 years, but commissioning had to be delayed for about three months due to problems with the apogee propulsion system: apparently, the main engine Leros 1c manufactured by Moog did not work properly, so auxiliary engines of the reactive control system were used to transfer the apparatus from geo-transition to geostationary orbit.

In January 2017, the satellite began broadcasting from a position at 60° East in geostationary orbit. Later on, they found out that Intelsat 33e was using more propellant than originally intended to keep its position. Consequently, Intelsat announced that the satellite would have its lifespan reduced by three and a half years.

A similar Intelsat 29e, launched on January 27, 2016, “underwent an anomaly” four months later due to a propulsion system fuel leak. The interruption of customer service was due to unstable communication with the satellite.

After another three years, ground-based telescopes detected numerous fragments around Intelsat 29e. The apparatus was spinning on its axis and drifting eastward. On April 18, 2019, Intelsat released a statement announcing the complete loss of the satellite.

Experts believed that the propulsion system failure could have occurred due to a collision with a micrometeorite, or due to a short circuit caused by solar activity, or due to problems with the cabling inside the spacecraft.

Intelsat 29e and 33e belong to the EpicNG (Epic Next Generation) series, currently consisting of six.

What is remarkable about this case is not only that the protagonist of the unfortunate events is once again Boeing, but also that the explosion of a geostationary satellite is an unusual phenomenon. Unlike most low-Earth orbit vehicles, geostationary heavy-lifters carry a significant amount of fuel at launch, which is used to “round” the orbit with one or more maneuvers, as well as to keep the satellite stationary.

Therefore, fuel leaks and vehicle destruction do occur in geostationary orbits, but not as often as in lower orbits. For example, in June 2016, several fragments separated from the Chinese satellite Beidou G2, and a fuel leak, were detected earlier. However, the vehicle did not fly apart, and in January 2022 the Shijian 21 tugboat took it to a burial orbit beyond the geostationary.

A much more frequent phenomenon is the destruction of upper stages (upper stages), which are used to launch satellites into geo-transition orbits. Since the rocket boosters are not directly in GEO, they themselves do not interfere with the communications vehicles, but they can seriously affect this orbit after destruction due to the debris produced during the explosion, which has different speeds and directions of motion.

For example, since 2018, four Centaur upper stages left in geo-transition orbit after ULA’s Atlas V launches have exploded in orbit. Each rocket unit ejected between 600 and 900 fragments after “disintegrating.”

Although the original orbit of the stages was far from the geostationary orbit, fragment orbits can pass dangerously close to operational spacecraft. Fortunately, the inclination of the stage orbit is different from the geostationary orbit, which explains why no collisions have occurred so far. However, one of the versions of the cause of the explosion of Intelsat 33e is precisely the collision with the rocket stage debris, which hit GEO from the geo-transition orbit.

The Intelsat 33e explosion itself is an even more dangerous event. This heavy satellite has become a real anti-satellite weapon.

The explosion of the apparatus weighing more than 4 tons generated hundreds of rather large debris with high velocity, which can not only damage, but completely destroy communication satellites in geostationary orbit.